‘The rules!’ shouted Ralph, ‘you’re breaking the rules’

As a young ‘specky-four-eyes’ I identify with Piggy in Lord of the Flies when his glasses get broken, but there’s a lot of Jack in me too. I’ve always thought rules weren’t for me. It occurred to me fairly early on in life that rules were generally arbitrary, were designed to suit the people that made them, and were mostly prejudicial to the people they were made against, i.e. me.

There was an experiment in the Netherlands recently: they removed the traffic lights and all the road markings from a few busy junctions to see what would happen, and the answer was ‘less than usually happened’ – people used common sense, caution and even politeness, and there were fewer accidents than usual.

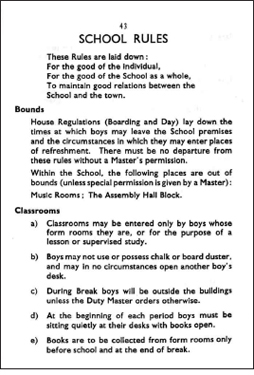

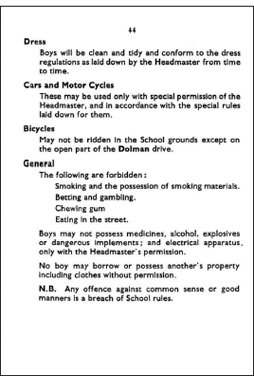

When I get to Pocklington we’re given a little booklet at the beginning of every term. It’s blue, and is simply called the Blue Book – it holds details of who’s in which form, sports fixtures, exam schedules, even the dates the barbers are coming to make us look more like convicts – and at the back there’s a list of rules, two pages of them, and it becomes a game really, to see how quickly we can break them. ‘Boys may not use or possess chalk or a board duster’, tick. ‘Boys will be clean and tidy and conform to the dress regulations laid down by the headmaster’, tick. ‘The following are forbidden: smoking, gambling, chewing gum, eating in the street’, tick, tick, tick, tick. If the rules weren’t there, we might be better behaved.

Then I discover that all the lessons are full of rules as well.

When I arrive at Pocklington Grammar School for Boys I’m a year behind in practically everything. I’ve spent a year at Hutton Junior High in Bradford but they haven’t taught me anything that the boys at Pocklington have learned. Principally I don’t know any grammar. It’s a grammar school and I’ve never been taught any of it, in fact I don’t know what it is. Everyone else has had at least a year, some boys who’ve been in the prep school have been learning grammar for five years.

I’m suddenly thousands of miles away from my parents, and the new people in charge of me – and my new schoolmates – are basically speaking a different language. It’s quite alienating, and I begin to feel rather alone.

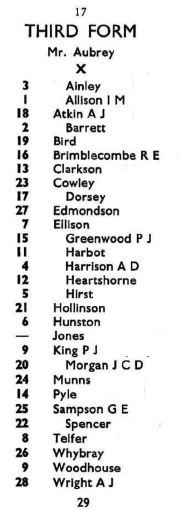

The Blue Book is not only full of school rules and sports fixtures, in the list of boys in each form there is a handy number printed beside your name. This is your academic ranking based on the previous year. Printing this in a book handed to every pupil makes it much easier for everyone else to see that, after my first year at the school, I’m 27th out of 29. Though in fact one boy doesn’t have any ranking at all, because he was in hospital for a long period, so I’m 27th out of 28. Second to bottom. I am officially thick. The indented names indicate day boys – non-boarders – and it’s interesting to see that the non-abandoned boys hold all the positions from 1 to 5.

I don’t know how we were taught French at my previous school. I remember a tape machine, and some slides, and repeating things parrot fashion. I’m pretty sure that the bakery is next door to the church and that the grocer’s is opposite the butcher’s – though I’m aware that this will only come in handy if I go to a town where the geographical layout precisely matches my French.

I’ve never heard the words verb, noun, object or subject, and the words pluperfect and transitive fill me with fear to this day. Luckily I’ve scraped through life without ever having to explain the difference between a gerund and a gerundive.

It should come as no surprise that grammar schools love grammar – and that they use it in everything. They use it most particularly in English, French and Latin, but even my history and geography homework is littered with red pen underlinings from the teachers and GRAMMAR! written angrily in the margin.

Latin is a complete mystery – I was going to say it’s all Greek to me, but that would have been a vast improvement in my skill set. My Latin teacher uses the ‘intimidation method’. He thinks I will learn if he shouts loudly at me, but this doesn’t work. ‘Conjugate!’ he will yell, apropos of nothing. I am nonplussed. ‘Decline!’

I do eventually decline. I decline to pay much attention. In one lesson he catches me threading a conker and brings me out to the front. He makes me finish threading it and insists I secure it with a good knot. Then he takes the conker and asks me to either decline or conjugate a verb – whichever – and every time I get it wrong he swings the conker on its string in a long arc and brings it down on my head.

It hurts. It hurts a great deal. It only takes a few blows before I start to cry. He thinks this is hilarious . . . but my classmates don’t. It’s an odd moment. He expects them to be on his side. Bullies do, don’t they? But they look at him with distaste. They think he’s gone too far. They know how much a conker can hurt. They daren’t voice their contempt in case he then picks on them, but he soon becomes aware of the lack of support. It unsettles him. He gives me a final clonk, not quite as hard this time, as if it’s just a bit of fun, and sends me back to my seat.

‘Let that be a lesson to you,’ he grins.

I learn nothing except hatred, and a lifelong fear of declining, or conjugating, whichever it is. But here’s a thing – why is the first verb I learn ‘amare’?

| Amo | I love |

| Amas | You love (singular) |

| Amat | He/she/it loves |

| Amamus | We love |

| Amatis | You love (plural) |

| Amant | They love |

The verb TO LOVE! Oh, the irony. It’s still the only Latin verb I know.

Years later when I take my Latin O-level – I cheat. I smuggle in a crib sheet and do a near-perfect translation of part of Julius Caesar’s De Bello Gallico – his account of the Gallic wars. I’m not stupid, I put in a couple of mistakes so that it doesn’t look too suspicious. I’m expected to fail completely but I get a three (one is excellent, seven a pass). When the results are posted, the bully teacher finds me in a corridor and expresses surprise but also delight that his harsh teaching methods have borne such fruit. I hate him even more, but I’m pleased to see that I’ve successfully pulled the wool over his eyes. ‘Veni, vidi, vici, twatface!’ Decline that.

How did you get in to Pocklington Grammar if you didn’t know any grammar?

Good question.

Imagine the scene. It’s 1968, we’re back in England having returned from Bahrain the year before, and I’m sitting the 11-plus. I’m in a classroom. Serried ranks of desks. It’s some kind of multiple-choice booklet and I’ve finished. I look around – no one else has finished. I look at the clock – there’s still twenty minutes to go! God, I must be brainy. Much brainier than these other thickos, one of whom is my cousin Kevin. Well, this must finally settle the question as to which of us is the brightest. Look at him, toiling over his answers. You can almost see the beads of sweat springing from his forehead, like an illustration in Tintin.

I’m bored. I flick my pen about. I use it like a drumstick on the desk. The invigilator tells me to stop. I lean back, hands behind my head, making exaggerated sighs of boredom. With about a minute to go the invigilator says ‘there’s about a minute to go’, and that we ought to make sure our names are written clearly on the front. I check the front, there’s my name. Duh! Course it’s there. I idly flick through the booklet. Look at all those answers – I’m pretty sure they’re nearly all correct, and that the ones I’ve taken a punt on are damn good guesses. Hang on . . . What’s this? Two of the pages seem to be stuck together. I prise them apart. What? Two pages of questions I haven’t answered? Two pages I haven’t even seen? They were stuck together! Two pages out of a total of eight pages. That’s a quarter of the entire exam I’ve missed (good at maths, you see). I panic. I feverishly reach for my pen. I look at the first question . . . and that’s when I’m told the exam is over. Kevin gets into Bradford Grammar. I don’t. I go to Hutton Junior High. Quite rightly. I mean what kind of arrogant thicko thinks he can answer all the questions twenty minutes quicker than everyone else?

Of course, as you know (do keep up 5C), Dad gets the job in Uganda soon after – if you’re having trouble keeping up with my family’s movements around the globe let me tell you the feeling’s mutual.

When they decide to pack me off to boarding school I sit another exam, an entrance exam, and get in to Pocklington, a very minor public school halfway between York and Hull – or, as the joke went, halfway between York and Hell – a school which seems to take a lot of expat and army ‘brats’, as we are charmingly called.

It’s a direct grant school, which in 1969 means that they give free places to a quarter of their intake as long as they’ve been at state schools up to that point. And I qualify! This is social mobility in action; a definite move from lower middle class to upper middle class. I’ve looked it up and 3.1 per cent of secondary pupils go to direct grant schools in the late sixties, which means I’m one of the 3.1 per cent of the socially mobile! Where’s my top hat?

But no, nobody has a top hat at school. Nobody has anything much. We’re sent to school with one trunk – basically a large suitcase. In this we have our school uniform, our sports kit, and some regulation ‘casual wear’: a sports jacket, a pair of ‘slacks’, and a shirt. We then have a satchel or briefcase with pencils, a geometry set and an Osmiroid fountain pen with blue ink and an italic nib. Everything is precisely stipulated, everything is named, and everything has a place. There’s a locker for clothing, a boot room for shoes, and a shared study for stationery items.

Everything at school is designed to stop you thinking for yourself. You never have to worry about what to wear because you don’t have any choice. Even the colour of our underwear is prescribed. You never have to worry about your things because you don’t have any things. The plan is to mould us all into exactly the same person: a well-educated, upper-middle-class empire builder who isn’t worried about being transported 6,000 miles away from his family to live with 600 strangers, none of whom will ever love him.

Of course, it takes some boys longer to become cold-hearted bastards than others.

The school knows this and they’ve developed their pastoral methods for dealing with it; which are a) never to mention it, and b) to fill in all the time so that there’s absolutely no chance to reflect.

Weekdays are taken up with lessons, then supervised homework, supervised baths, supervised bed and supervised lights out. There’s a lot of supervision. And the weekends are no different. On Saturday there’s school in the morning, games in the afternoon, and compulsory ‘TV’ in the evening, and on Sunday there’s compulsory church, compulsory ‘writing letters home’ after lunch, and a compulsory ‘nap’ in the late afternoon. There’s a lot of compulsion. This is why public-school boys do quite well in the armed forces and in prison.

During our ‘nap’ some of us listen to the chart countdown on small transistor radios hidden under our pillows. My first year there is the year when the chart is truly eclectic. In 1969 the top spot is shared between The Scaffold, Marmalade, Fleetwood Mac, The Move, Amen Corner, Peter Sarstedt, Marvin Gaye, Desmond Dekker, The Beatles (with Billy Preston) – that’s some billing – Tommy Roe (‘Dizzy’), Thunderclap Newman, The Rolling Stones, Zager and Evans (you think you don’t know – ‘In the Year 2525’), Creedence Clearwater Revival, Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg getting all steamy and suggestive, Bobbie Gentry, Rolf Harris and . . . oh. Not allowed to mention Rolf.

It’s 1969! It’s the end of the sixties! But while the rest of the world is flailing around in an orgy of free love, self-expression and hallucinogenic drugs – I’m listening to Radio 1, at very low volume, wearing a sports jacket and casual slacks. I’m trapped in a small prison learning to repress my emotions. Turns out I’m bloody good at it. If the 11-plus had been about repression I would have passed no problem.

Repression is good for trainee berserkers. It builds up like a pressure cooker until you don’t know what you’re thinking. And as the teachers know – thinking is dangerous.